Unearthing climate change challenges along Delaware Bayshore

By Guest Contributor | April 19, 2024

GREAT LAKES ECHO – Greatlakesecho.org - David Poulson – 517-432-5417

Shane Godshall speaks to a group of journalists about his work doing habitat restoration on Money Island. Image: Christa Young

By Christa Young

Editor’s note: This is one in a series of stories coming out of a recent meeting of the Society of Environmental Journalists in Philadelphia.

New Jersey’s Delaware Bayshore isn’t called the road less traveled without reason. Persistent rainfall, exacerbated by global warming, has increased the wetlands in this area of Cumberland County. Journalists, scientists, and conservationists are uncovering data showing that remote rural communities like Money Island will be flooded soon if politicians and state officials don’t act fast. Roughly three dozen attendees of the recent Society of Environmental Journalists annual conference in Philadelphia traveled to Money Island, the smallest and most remote rural hamlet in the county. It was the first stop on a daylong traverse of a 70-mile stretch of untouched Delaware Bayshore coastline in southeast New Jersey.

They met Tony Novak, a longtime resident and controller of BaySave, a nonprofit organization that focuses on sustainability. Novak, who has called the island home for three decades, highlighted the rapid erosion caused by rising sea levels, placing homes at risk of significant damage and deterioration. Novak once traveled with what was then referred to as the Community Sea Level Rise Response Team, a group that brought attention to the swift land degradation to local government officials. The group was often met with disfavor.

In 2018, New Jersey sued Novak, BaySave, his children, his father and other nonprofit organizations, for allegedly not acquiring the proper permits for filling in the wetlands. Novak said the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection is intentionally denying specific permit requests as one of many tactics to prevent the stabilization of Money Island.

Residents of Delaware Bay posted signs on their homes and mailboxes that displayed “No Retreat Save Bayshore Communities” to express their hope concerning the future of their Bayshore community. While Novak’s team, Bayshore, and other partners continue to fight for the livelihood of the Island, water levels continue to rise, signaling the need for action to protect the land and its inhabitants.

Novak said that he was viewed by state officials as making too much ‘noise’ about the environmental decay of Money Island. Many of the affected homes were weekend retreats for families from the southern part of the states. Residents were presented with buyout offers as part of an ongoing demolition led by New Jersey. This is done through a program known as Blue Acres, which frees up the land to function as natural flood storage, wetlands, or open space.

The journalists also heard from representatives of the American Littoral Society, which monitors the island and is restoring habitat for wildlife and promoting conservation. Habitat restoration project manager Shane Godshall said that his team facilitated dredging a channel on Money Island to create a habitat for horseshoe crabs and a bird called the red knot.

“Essentially what was here before was not conducive to horseshoe crabs,” Novak said. Now, to use the space, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection is taking down homes to restore the land to habitat for the crabs and the birds that are keystone species for the bay. Novak acknowledged that the future of Money Island is uncertain and that he doesn’t have high expectations for the local government to provide help for the island. ‘‘My plan is just to go to a slow, soft footprint,” he said. Enjoy what we have here. “It’s a wonderful place,” he added, “until the bugs show up.”

By Guest Contributor | April 19, 2024

GREAT LAKES ECHO – Greatlakesecho.org - David Poulson – 517-432-5417

Shane Godshall speaks to a group of journalists about his work doing habitat restoration on Money Island. Image: Christa Young

By Christa Young

Editor’s note: This is one in a series of stories coming out of a recent meeting of the Society of Environmental Journalists in Philadelphia.

New Jersey’s Delaware Bayshore isn’t called the road less traveled without reason. Persistent rainfall, exacerbated by global warming, has increased the wetlands in this area of Cumberland County. Journalists, scientists, and conservationists are uncovering data showing that remote rural communities like Money Island will be flooded soon if politicians and state officials don’t act fast. Roughly three dozen attendees of the recent Society of Environmental Journalists annual conference in Philadelphia traveled to Money Island, the smallest and most remote rural hamlet in the county. It was the first stop on a daylong traverse of a 70-mile stretch of untouched Delaware Bayshore coastline in southeast New Jersey.

They met Tony Novak, a longtime resident and controller of BaySave, a nonprofit organization that focuses on sustainability. Novak, who has called the island home for three decades, highlighted the rapid erosion caused by rising sea levels, placing homes at risk of significant damage and deterioration. Novak once traveled with what was then referred to as the Community Sea Level Rise Response Team, a group that brought attention to the swift land degradation to local government officials. The group was often met with disfavor.

In 2018, New Jersey sued Novak, BaySave, his children, his father and other nonprofit organizations, for allegedly not acquiring the proper permits for filling in the wetlands. Novak said the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection is intentionally denying specific permit requests as one of many tactics to prevent the stabilization of Money Island.

Residents of Delaware Bay posted signs on their homes and mailboxes that displayed “No Retreat Save Bayshore Communities” to express their hope concerning the future of their Bayshore community. While Novak’s team, Bayshore, and other partners continue to fight for the livelihood of the Island, water levels continue to rise, signaling the need for action to protect the land and its inhabitants.

Novak said that he was viewed by state officials as making too much ‘noise’ about the environmental decay of Money Island. Many of the affected homes were weekend retreats for families from the southern part of the states. Residents were presented with buyout offers as part of an ongoing demolition led by New Jersey. This is done through a program known as Blue Acres, which frees up the land to function as natural flood storage, wetlands, or open space.

The journalists also heard from representatives of the American Littoral Society, which monitors the island and is restoring habitat for wildlife and promoting conservation. Habitat restoration project manager Shane Godshall said that his team facilitated dredging a channel on Money Island to create a habitat for horseshoe crabs and a bird called the red knot.

“Essentially what was here before was not conducive to horseshoe crabs,” Novak said. Now, to use the space, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection is taking down homes to restore the land to habitat for the crabs and the birds that are keystone species for the bay. Novak acknowledged that the future of Money Island is uncertain and that he doesn’t have high expectations for the local government to provide help for the island. ‘‘My plan is just to go to a slow, soft footprint,” he said. Enjoy what we have here. “It’s a wonderful place,” he added, “until the bugs show up.”

Groups Seek Federal Protection for Horseshoe Crabs

by Frank Graff - Published on April 19, 2024 • Last modified on April 15, 2024

SCIENCE & NATURE

Modern Needs Threaten an Ancient Creature

If you happen to come across a horseshoe crab shell while walking along the beach, you might think you’ve just discovered a creature related to the dinosaurs. You would be close, sort of.

Scientists have discovered fossils of early horseshoe crabs that lived 445 million years ago. Dinosaurs first appeared roughly 200 million years later. Bottom line, you could call a horseshoe crab a living fossil. Four species of horseshoe crab are found today: one is found in Atlantic coastal waters and the Gulf of Mexico, and the other three are found along Asia’s coastal waters.

But while horseshoe crabs may have survived the extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs, they’re not doing as well surviving humans.

That’s because horseshoe crab blood contains a unique enzyme called limulus amebocyte lysate, or LAL. This substance causes the blood to coagulate when exposed to toxins. Biomedical companies use LAL to test medicines, vaccines, implants and more for toxins. That’s also how they ensure medical equipment is safe for people.

Nearly one million horseshoe crabs were harvested for their blood in 2022, according to the Center for Biological Diversity. Unfortunately, many horseshoe crabs die in the process of blood harvesting.

“We’re wiping out one of the world’s oldest and toughest creatures,” said Will Harlan, a senior scientist at the center, in a release. “These living fossils urgently need Endangered Species Act protection. Horseshoe crabs have saved countless lives, and now we should return the favor.” The center is joined by 22 other organizations in petitioning the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to list American horseshoe crabs under the Endangered Species Act as an endangered or threatened species.

“The continued reliance on horseshoe crab blood by pharmaceutical manufacturers has led to a rapid decrease in the population of this important species,” said Kathleen Conlee, vice president for animal research issues with the Humane Society of the United States. “Fortunately, there are non-animal alternatives that can replace the use of horseshoe crab blood and help protect these amazing animals from further overharvest.” The groups maintain synthetic alternatives are being used in Europe.

Watch this Sci NC story about how a North Carolina company is working to create an alternative to horseshoe crab blood for medical research:

How horseshoe crabs save lives Every time you get a flu shot, you should thank a horseshoe crab.

More threats to horseshoe crabs

In addition to medical research, horseshoe crabs are also harvested for bait by several commercial fisheries. But it’s not just harvesting that threatens the brown, body-armored animals. Horseshoe crabs have also lost spawning grounds all along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts where they lay their eggs. The petition cites coastal development, shoreline hardening (the building of walls and other engineered structures along the coast to prevent erosion) and sea-level rise. In fact, the largest populations, which are found in Delaware Bay, have declined by two-thirds in the last 30 years. Groups also say the decline in horseshoe crabs threatens other species. One horseshoe crab can lay about 4,000 eggs. And shorebirds rely on those eggs and newly hatched crabs for food.

“Horseshoe crab eggs are incredibly nutrient dense, sustaining [birds like] the federally threatened red knot on their long migration journey,” said Steve Holmer, vice president of policy at American Bird Conservancy. “Greater protection of the horseshoe crab is needed to fully recover the red knot, as well as conserve other shorebird species.” While populations of horseshoe crabs in North America are in decline, a sister species, the tri-spine horseshoe crab in Asia, faces similar threats and is nearly extinct.

“It is clear from the available science that current fisheries management practices are failing to protect and sustain these ancient mariners,” said Tim Dillingham, executive director of the American Littoral Society. “We must do more to keep them and the red knots and other life that depend on horseshoe crabs from disappearing from this Earth.”

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

Listing horseshoe crabs under Endangered Species Act won’t close beaches

By Will Harlan -April 12, 2024

I appreciated Eric Burnley's thoughts on horseshoe crabs and their importance to the people of Delaware Bay. He powerfully describes the steep declines in horseshoe crabs and rightfully calls for the end of bottom trawling and a ban on horseshoe crab bait harvests.

I just wanted to offer one clarification: Listing horseshoe crabs under the Endangered Species Act will not close beaches. It might lead to stricter limits on commercial horseshoe crab harvests but would not have any effect on visitor beach access.

Recreational fishing of Delaware beaches would be significantly improved by listing horseshoe crabs. As Burnley observes, numerous species of fish feed on horseshoe crab eggs. If horseshoe crabs return to abundance, so will many species of fish, shorebirds, sea turtles and other wildlife.

Will Harlan

Senior Scientist Center for Biological Diversity - Wilmington, DE

A letter to the editor expresses a reader's opinion and, as such, is not reflective of the editorial opinions of this newspaper. To submit a letter to the editor for publishing, send an email to [email protected]

by Frank Graff - Published on April 19, 2024 • Last modified on April 15, 2024

SCIENCE & NATURE

Modern Needs Threaten an Ancient Creature

If you happen to come across a horseshoe crab shell while walking along the beach, you might think you’ve just discovered a creature related to the dinosaurs. You would be close, sort of.

Scientists have discovered fossils of early horseshoe crabs that lived 445 million years ago. Dinosaurs first appeared roughly 200 million years later. Bottom line, you could call a horseshoe crab a living fossil. Four species of horseshoe crab are found today: one is found in Atlantic coastal waters and the Gulf of Mexico, and the other three are found along Asia’s coastal waters.

But while horseshoe crabs may have survived the extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs, they’re not doing as well surviving humans.

That’s because horseshoe crab blood contains a unique enzyme called limulus amebocyte lysate, or LAL. This substance causes the blood to coagulate when exposed to toxins. Biomedical companies use LAL to test medicines, vaccines, implants and more for toxins. That’s also how they ensure medical equipment is safe for people.

Nearly one million horseshoe crabs were harvested for their blood in 2022, according to the Center for Biological Diversity. Unfortunately, many horseshoe crabs die in the process of blood harvesting.

“We’re wiping out one of the world’s oldest and toughest creatures,” said Will Harlan, a senior scientist at the center, in a release. “These living fossils urgently need Endangered Species Act protection. Horseshoe crabs have saved countless lives, and now we should return the favor.” The center is joined by 22 other organizations in petitioning the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to list American horseshoe crabs under the Endangered Species Act as an endangered or threatened species.

“The continued reliance on horseshoe crab blood by pharmaceutical manufacturers has led to a rapid decrease in the population of this important species,” said Kathleen Conlee, vice president for animal research issues with the Humane Society of the United States. “Fortunately, there are non-animal alternatives that can replace the use of horseshoe crab blood and help protect these amazing animals from further overharvest.” The groups maintain synthetic alternatives are being used in Europe.

Watch this Sci NC story about how a North Carolina company is working to create an alternative to horseshoe crab blood for medical research:

How horseshoe crabs save lives Every time you get a flu shot, you should thank a horseshoe crab.

More threats to horseshoe crabs

In addition to medical research, horseshoe crabs are also harvested for bait by several commercial fisheries. But it’s not just harvesting that threatens the brown, body-armored animals. Horseshoe crabs have also lost spawning grounds all along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts where they lay their eggs. The petition cites coastal development, shoreline hardening (the building of walls and other engineered structures along the coast to prevent erosion) and sea-level rise. In fact, the largest populations, which are found in Delaware Bay, have declined by two-thirds in the last 30 years. Groups also say the decline in horseshoe crabs threatens other species. One horseshoe crab can lay about 4,000 eggs. And shorebirds rely on those eggs and newly hatched crabs for food.

“Horseshoe crab eggs are incredibly nutrient dense, sustaining [birds like] the federally threatened red knot on their long migration journey,” said Steve Holmer, vice president of policy at American Bird Conservancy. “Greater protection of the horseshoe crab is needed to fully recover the red knot, as well as conserve other shorebird species.” While populations of horseshoe crabs in North America are in decline, a sister species, the tri-spine horseshoe crab in Asia, faces similar threats and is nearly extinct.

“It is clear from the available science that current fisheries management practices are failing to protect and sustain these ancient mariners,” said Tim Dillingham, executive director of the American Littoral Society. “We must do more to keep them and the red knots and other life that depend on horseshoe crabs from disappearing from this Earth.”

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

Listing horseshoe crabs under Endangered Species Act won’t close beaches

By Will Harlan -April 12, 2024

I appreciated Eric Burnley's thoughts on horseshoe crabs and their importance to the people of Delaware Bay. He powerfully describes the steep declines in horseshoe crabs and rightfully calls for the end of bottom trawling and a ban on horseshoe crab bait harvests.

I just wanted to offer one clarification: Listing horseshoe crabs under the Endangered Species Act will not close beaches. It might lead to stricter limits on commercial horseshoe crab harvests but would not have any effect on visitor beach access.

Recreational fishing of Delaware beaches would be significantly improved by listing horseshoe crabs. As Burnley observes, numerous species of fish feed on horseshoe crab eggs. If horseshoe crabs return to abundance, so will many species of fish, shorebirds, sea turtles and other wildlife.

Will Harlan

Senior Scientist Center for Biological Diversity - Wilmington, DE

A letter to the editor expresses a reader's opinion and, as such, is not reflective of the editorial opinions of this newspaper. To submit a letter to the editor for publishing, send an email to [email protected]

Parts of Jersey Shore beaches will be closed past Memorial Day after storm causes erosion

Published: May. 13, 2022, 1:56 p.m.

By Jeff Goldman | NJ Advance Media for NJ.com

Beach erosion following last weekend’s fierce coastal storm has created additional headaches in several towns with Memorial Day weekend only two weeks away.

The Ortley Beach section of Toms River, North Wildwood and Stone Harbor are among the places where tides and strong winds took their toll — wiping away massive amounts of sand, and producing “cliffs” near the diminished dunes, officials in those towns said.

There was also beach erosion in Brigantine, according to Real Brigantine, a local news website. Town officials there couldn’t be reached by NJ Advance Media.

Ortley Beach experienced erosion primarily between 4th Street and 8th Street and will need to spend approximately $200,000 to replenish lost sand, Mayor Maurice “Mo” Hill said in a phone interview Thursday.

When Memorial Day weekend rolls around, about 75% of the beach will be accessible, with the rest closed off because there won’t be walkovers due to the cliffs, which are currently about 5 to 6 feet high, the mayor said. The township council expects to award a contract at its meeting on May 25 meeting with construction beginning shortly thereafter. Work to replace the sand will take about 2 to 3 weeks.

“We’ll be completed by mid-June when school is letting out and the season is starting to really heat up,” Hill said.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is scheduled to return to Ortley Beach “late this year or early next year” for the next phase of its replenishment project, the mayor said. That is part of a long-term periodic nourishment following the completion of a big beach replenishment between Manasquan Inlet to Barnegat Inlet that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers completed in July 2019.

Near the southern tip of the state, North Wildwood lost about one-third of the roughly $4 million in sand it had piled up to refurbish its beaches, Mayor Patrick Rosenello said. While some sand that settled in the ocean close to the shore will eventually push back onto the beach, much of it might be gone for good.

Beaches between 3rd Avenue and 7th Avenue lost a significant amount of sand. Beaches from 7th Avenue to 15hth Avenue also took a hit. One cliff is about 20 feet high, the mayor said.

Portions of the beach will not be ready to open for the holiday weekend and those areas will be clearly marked, Rosenello said.

“The storm has caused a major delay in our project,” said Rosenello in explaining that each spring North Wildwood trucks in sand from Wildwood. Work was suspended in the days leading up to the storm and hasn’t been able to resume this week due to winds and the ocean being so high.

North Wildwood is also in the midst of a long-term project being handled by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

“North Wildwood is experiencing significant erosion of its berm and dune,” the corps said in July 2021. “What was the largest beach in the state now suffers from tidal flooding and wave run-up over a formerly protective beach. North Wildwood has lost approximately 1,000 feet of beach during the past 5-10 years.”

In Stone Harbor, meanwhile, “significant” erosion took place between 90th and 111th Streets, according to Mayor Judith Davies-Dunhour.

“It is still too early to report on the exact quantity of sand that was lost, but we do know that that a few feet of dunes were cut back on the seaward side and beach elevation was reduced,” Davies-Dunhour said in an emailed statement.” Once tide levels return to normal, some natural beach regeneration is anticipated, as sand that has been temporarily deposited in deeper water returns to the beach.”

The borough said it will replace sand on a small scale before the holiday weekend with a beach fill project planned for later in the year.

In addition, the Stockton University Coastal Research Center will perform emergency beach surveys to determine total beach loss in Stone Harbor, starting as soon as next week.

Other places fared better. While North Wildwood has a big replenishment job ahead, Wildwood was spared, a spokeswoman said. So was one of the most popular spots in Ocean County — Seaside Heights.

“We lucked out,” Seaside Heights Mayor Tony Vaz said. “We’re good, thank God.”

Island Beach State Park experienced minor erosion but no beach closures are expected on Memorial Day weekend, a spokeswoman for the state Department of Environmental Protection said.

Published: May. 13, 2022, 1:56 p.m.

By Jeff Goldman | NJ Advance Media for NJ.com

Beach erosion following last weekend’s fierce coastal storm has created additional headaches in several towns with Memorial Day weekend only two weeks away.

The Ortley Beach section of Toms River, North Wildwood and Stone Harbor are among the places where tides and strong winds took their toll — wiping away massive amounts of sand, and producing “cliffs” near the diminished dunes, officials in those towns said.

There was also beach erosion in Brigantine, according to Real Brigantine, a local news website. Town officials there couldn’t be reached by NJ Advance Media.

Ortley Beach experienced erosion primarily between 4th Street and 8th Street and will need to spend approximately $200,000 to replenish lost sand, Mayor Maurice “Mo” Hill said in a phone interview Thursday.

When Memorial Day weekend rolls around, about 75% of the beach will be accessible, with the rest closed off because there won’t be walkovers due to the cliffs, which are currently about 5 to 6 feet high, the mayor said. The township council expects to award a contract at its meeting on May 25 meeting with construction beginning shortly thereafter. Work to replace the sand will take about 2 to 3 weeks.

“We’ll be completed by mid-June when school is letting out and the season is starting to really heat up,” Hill said.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is scheduled to return to Ortley Beach “late this year or early next year” for the next phase of its replenishment project, the mayor said. That is part of a long-term periodic nourishment following the completion of a big beach replenishment between Manasquan Inlet to Barnegat Inlet that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers completed in July 2019.

Near the southern tip of the state, North Wildwood lost about one-third of the roughly $4 million in sand it had piled up to refurbish its beaches, Mayor Patrick Rosenello said. While some sand that settled in the ocean close to the shore will eventually push back onto the beach, much of it might be gone for good.

Beaches between 3rd Avenue and 7th Avenue lost a significant amount of sand. Beaches from 7th Avenue to 15hth Avenue also took a hit. One cliff is about 20 feet high, the mayor said.

Portions of the beach will not be ready to open for the holiday weekend and those areas will be clearly marked, Rosenello said.

“The storm has caused a major delay in our project,” said Rosenello in explaining that each spring North Wildwood trucks in sand from Wildwood. Work was suspended in the days leading up to the storm and hasn’t been able to resume this week due to winds and the ocean being so high.

North Wildwood is also in the midst of a long-term project being handled by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

“North Wildwood is experiencing significant erosion of its berm and dune,” the corps said in July 2021. “What was the largest beach in the state now suffers from tidal flooding and wave run-up over a formerly protective beach. North Wildwood has lost approximately 1,000 feet of beach during the past 5-10 years.”

In Stone Harbor, meanwhile, “significant” erosion took place between 90th and 111th Streets, according to Mayor Judith Davies-Dunhour.

“It is still too early to report on the exact quantity of sand that was lost, but we do know that that a few feet of dunes were cut back on the seaward side and beach elevation was reduced,” Davies-Dunhour said in an emailed statement.” Once tide levels return to normal, some natural beach regeneration is anticipated, as sand that has been temporarily deposited in deeper water returns to the beach.”

The borough said it will replace sand on a small scale before the holiday weekend with a beach fill project planned for later in the year.

In addition, the Stockton University Coastal Research Center will perform emergency beach surveys to determine total beach loss in Stone Harbor, starting as soon as next week.

Other places fared better. While North Wildwood has a big replenishment job ahead, Wildwood was spared, a spokeswoman said. So was one of the most popular spots in Ocean County — Seaside Heights.

“We lucked out,” Seaside Heights Mayor Tony Vaz said. “We’re good, thank God.”

Island Beach State Park experienced minor erosion but no beach closures are expected on Memorial Day weekend, a spokeswoman for the state Department of Environmental Protection said.

Can a sewer project keep a sleepy corner of rural New Jersey from fading away?

A $15 million sewer project is coming to Downe Township, a rural community along the Delaware Bay in Cumberland County, New Jersey

Published January 22, 2022 ~ by Jason Nark Staff Writer Philadelphia Inquirer

DOWNE TOWNSHIP, N.J. — There are no neon lights, no boardwalk, and amusements include the constant lapping waves of the Delaware Bay and the occasional sight of a thousand snow geese flying over the salt marshes like windswept clouds.

For the 1,500 or so people who live in this rural Cumberland County community, 60 miles south of Philadelphia, life without a traffic light is the way they like it. But many of Downe’s unincorporated communities, like the centuries-old fishing villages of Fortescue and Money Island, and the single road of bayfront homes on Gandy’s Beach, were hammered by Hurricane Irene and Superstorm Sandy.

A few dozen Money Island homeowners sold their properties to the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection in the aftermath of those storms, and others are negotiating to do the same. Once the DEP razes those homes, the properties will essentially go back to nature. That’s what happened in Seabreeze, a ghost town just north of Downe, where every home is gone.

“That’s not going to happen here. We won’t let it,” Downe Township Mayor Mike Rothman said aboard his fishing boat in Fortescue recently. Rothman and former Mayor Robert Campbell believe their longtime dream -- replacing septic systems and propane tanks with sewer lines and natural gas -- will be a bulwark against the forces of nature and a rebuttal to those who feel the residents of Downe should retreat from the coast and move inland. The project is finally coming to fruition for Fortescue and Gandy’s Beach, and Campbell believes the consistency and cost benefits of modern infrastructure could boost property values and draw in new businesses like hotels and eateries.

“Honestly, I’d love to see an ice cream parlor,” Campbell, now a committeeman in Downe, said. “There’s no place to get an ice cream cone in Fortescue.”

"Rothman said one potential buyer is interested in building a

100-room hotel at the current site of a campground on the water."

The sewer project, which could go out to bid in the coming months, has been discussed for a decade and is estimated to cost $15 million. Downe Township received a $4.49 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 2019 for construction costs. Approximately $11 million of the project is funded via grants, Campbell said, and the rest could be financed if more grants are unavailable. The sewer plant will be built at the site of a former boatyard in Fortescue purchased by the township.

Campbell said there have been a few “naysayers” but estimated that 99% of the public is on board. “There’s always people who don’t want any change,” he said.

When the USDA grant was announced in 2019, Jeff Tittel, the now-retired director of the New Jersey Sierra Club, wrote op-eds denouncing the project as a way to usher in unneeded development in one of the state’s most unique and fragile landscapes. “I still feel that way,” Tittel said recently.

New Jersey’s bayfront, Tittel said, is on the front lines of climate change and rising sea levels, prone to constant flooding and susceptible to major storms. He believes people should be slowly retreating from communities like Fortescue and Gandy’s Beach, not shoring up the infrastructure there. “We shouldn’t be investing in places like this,” he said, “because they might not be here in 50 years. They might be underwater.”

Rothman and Campbell say it’s defeatism, not climate change, that’s the real threat to Downe Township. “We have the same flooding we’ve always had,” Campbell said. “It’s mother nature.”

Jane Morton Galetto, board president of Citizens United to Protect the Maurice River & Its Tributaries, said Downe’s sewer project is preferable to the current situation, where the state of each property’s septic system can vary greatly. Communities like Fortescue are cultural anchors, Morton Galetto said, as important to Downe and New Jersey as all the township’s natural resources. “We are not a historical society, but we have a grand appreciation of people’s place in the landscape,” she said on a tour through Downe Township recently.

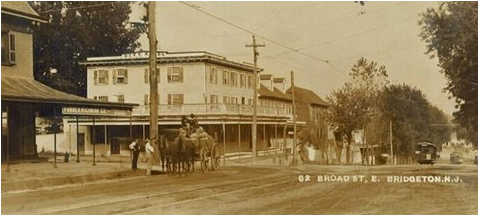

Fortescue has been a tourist attraction since the 1800s, accessible by buggy and boat. Hotels and dance halls and beachfront shacks rose and fell like the tides, sometimes burned to the ground or swept out by storms. The town is still known as the “weakfish capital of the world,” after the once bountiful fish that populated the water and dinner plates there.

Rothman, who owns a fishing charter boat he docks in Fortescue, said he takes nearly as many bird-watchers out for cruises these days as he does fishermen.

Some homes in Downe’s bayfront communities are vacant, or in disrepair, but officials believe that will change once sewer lines go to every property. Real estate sales are already increasing in Fortescue and Gandy’s Beach, Rothman said, and some agents have mentioned the infrastructure project in their listings. It’s possible to purchase a waterfront home in Fortescue for less than $300,000.

“I don’t think we’ll see the full impact until a year or two,” said Donald Sullivan, a real estate agent out of Vineland, “but I’ve already sold a few properties where the buyer was under the assumption this was going to happen. That was part of the deal.” Fortescue has a few eateries, summer-only merchants, and, of course, a bait shop. There are a handful of homes available on Airbnb in Downe and four rooms at the Charlesworth Hotel & Restaurant, a waterfront steak and seafood establishment built in 1924.

Rothman said one potential buyer is interested in building a 100-room hotel at the current site of a campground on the water.

The Charlesworth’s owner, Syboll, said he spends $2,000 a month on his septic system and is eager for the sewer project to get started.

Rothman said no sewer project will change the bucolic nature of Downe Township. Most of its land consists of inland farms, protected open space, and vast acreages owned by nonprofits like the Nature Conservancy and Natural Lands trust. Their bayfront communities serve a different crowd than the millions who head to the Jersey Shore every summer. “There may be development but, bottom line, this is still Fortescue,” he said. “It’s never going to be Wildwood or Cape May. We pride ourselves on nature. That’s why people are going to come here.”

A $15 million sewer project is coming to Downe Township, a rural community along the Delaware Bay in Cumberland County, New Jersey

Published January 22, 2022 ~ by Jason Nark Staff Writer Philadelphia Inquirer

DOWNE TOWNSHIP, N.J. — There are no neon lights, no boardwalk, and amusements include the constant lapping waves of the Delaware Bay and the occasional sight of a thousand snow geese flying over the salt marshes like windswept clouds.

For the 1,500 or so people who live in this rural Cumberland County community, 60 miles south of Philadelphia, life without a traffic light is the way they like it. But many of Downe’s unincorporated communities, like the centuries-old fishing villages of Fortescue and Money Island, and the single road of bayfront homes on Gandy’s Beach, were hammered by Hurricane Irene and Superstorm Sandy.

A few dozen Money Island homeowners sold their properties to the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection in the aftermath of those storms, and others are negotiating to do the same. Once the DEP razes those homes, the properties will essentially go back to nature. That’s what happened in Seabreeze, a ghost town just north of Downe, where every home is gone.

“That’s not going to happen here. We won’t let it,” Downe Township Mayor Mike Rothman said aboard his fishing boat in Fortescue recently. Rothman and former Mayor Robert Campbell believe their longtime dream -- replacing septic systems and propane tanks with sewer lines and natural gas -- will be a bulwark against the forces of nature and a rebuttal to those who feel the residents of Downe should retreat from the coast and move inland. The project is finally coming to fruition for Fortescue and Gandy’s Beach, and Campbell believes the consistency and cost benefits of modern infrastructure could boost property values and draw in new businesses like hotels and eateries.

“Honestly, I’d love to see an ice cream parlor,” Campbell, now a committeeman in Downe, said. “There’s no place to get an ice cream cone in Fortescue.”

"Rothman said one potential buyer is interested in building a

100-room hotel at the current site of a campground on the water."

The sewer project, which could go out to bid in the coming months, has been discussed for a decade and is estimated to cost $15 million. Downe Township received a $4.49 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 2019 for construction costs. Approximately $11 million of the project is funded via grants, Campbell said, and the rest could be financed if more grants are unavailable. The sewer plant will be built at the site of a former boatyard in Fortescue purchased by the township.

Campbell said there have been a few “naysayers” but estimated that 99% of the public is on board. “There’s always people who don’t want any change,” he said.

When the USDA grant was announced in 2019, Jeff Tittel, the now-retired director of the New Jersey Sierra Club, wrote op-eds denouncing the project as a way to usher in unneeded development in one of the state’s most unique and fragile landscapes. “I still feel that way,” Tittel said recently.

New Jersey’s bayfront, Tittel said, is on the front lines of climate change and rising sea levels, prone to constant flooding and susceptible to major storms. He believes people should be slowly retreating from communities like Fortescue and Gandy’s Beach, not shoring up the infrastructure there. “We shouldn’t be investing in places like this,” he said, “because they might not be here in 50 years. They might be underwater.”

Rothman and Campbell say it’s defeatism, not climate change, that’s the real threat to Downe Township. “We have the same flooding we’ve always had,” Campbell said. “It’s mother nature.”

Jane Morton Galetto, board president of Citizens United to Protect the Maurice River & Its Tributaries, said Downe’s sewer project is preferable to the current situation, where the state of each property’s septic system can vary greatly. Communities like Fortescue are cultural anchors, Morton Galetto said, as important to Downe and New Jersey as all the township’s natural resources. “We are not a historical society, but we have a grand appreciation of people’s place in the landscape,” she said on a tour through Downe Township recently.

Fortescue has been a tourist attraction since the 1800s, accessible by buggy and boat. Hotels and dance halls and beachfront shacks rose and fell like the tides, sometimes burned to the ground or swept out by storms. The town is still known as the “weakfish capital of the world,” after the once bountiful fish that populated the water and dinner plates there.

Rothman, who owns a fishing charter boat he docks in Fortescue, said he takes nearly as many bird-watchers out for cruises these days as he does fishermen.

Some homes in Downe’s bayfront communities are vacant, or in disrepair, but officials believe that will change once sewer lines go to every property. Real estate sales are already increasing in Fortescue and Gandy’s Beach, Rothman said, and some agents have mentioned the infrastructure project in their listings. It’s possible to purchase a waterfront home in Fortescue for less than $300,000.

“I don’t think we’ll see the full impact until a year or two,” said Donald Sullivan, a real estate agent out of Vineland, “but I’ve already sold a few properties where the buyer was under the assumption this was going to happen. That was part of the deal.” Fortescue has a few eateries, summer-only merchants, and, of course, a bait shop. There are a handful of homes available on Airbnb in Downe and four rooms at the Charlesworth Hotel & Restaurant, a waterfront steak and seafood establishment built in 1924.

Rothman said one potential buyer is interested in building a 100-room hotel at the current site of a campground on the water.

The Charlesworth’s owner, Syboll, said he spends $2,000 a month on his septic system and is eager for the sewer project to get started.

Rothman said no sewer project will change the bucolic nature of Downe Township. Most of its land consists of inland farms, protected open space, and vast acreages owned by nonprofits like the Nature Conservancy and Natural Lands trust. Their bayfront communities serve a different crowd than the millions who head to the Jersey Shore every summer. “There may be development but, bottom line, this is still Fortescue,” he said. “It’s never going to be Wildwood or Cape May. We pride ourselves on nature. That’s why people are going to come here.”

Dredging starts off Downe Township to make Nantuxent Creek easier to transit

Joseph P. Smith Vineland Daily Journal – 12/31/2021

DOWNE – Nantuxent Creek is getting its first man-made scouring in a $1.6 million effort to reverse what a decade of big storms have done to clog a key passage for commercial fishing and recreational boats using the Delaware Bay.

The New Jersey Department of Transportation on Wednesday disclosed the start of work. Its Office of Maritime Resources is leading the project in collaboration with several N.J. Department of Environmental Protection maritime and wildlife programs.

The storms that helped silt up the Nantuxent also battered Money Island, a small village at its entrance. Money Island is a principal port for boats supplying packing houses in nearby Port Norris with bay oysters. The project has some direct benefits for the island.

Bay shore frustrations bubble over in meeting with NJ commissioner

Joseph P. Smith Vineland Daily Journal - 12/31/2021

MAURICE RIVER – New Jersey’s top environmental official says the state is not ready to pay for immediate storm protection projects in this stretch of Delaware Bay shore, despite local officials reporting worsening safety conditions.

N.J. Department of Environmental Protection Commissioner Shawn M. LaTourette toured some trouble spots along the Maurice River last week. That was a popular move on his part among local officials, who still ended the day in disappointment.

LaTourette turned back requests to commit to anti-flooding projects, counseling instead greater planning coordination for a "holistic" view on the local level. Communities need to prepare for when money might become available, he said.

Maurice River Township hosted the tour and meeting, working with state Sen. Michael Testa, R-1, to arrange them. Representatives from Commercial and Downe townships and Cumberland County also attended.

"New Jersey’s top environmental official says the state is not ready to pay for

immediate storm protection projects in this stretch of Delaware Bay shore,

despite local officials reporting worsening safety conditions."

“It was very good that he showed up,” Mayor Ken Whilden said afterward. “Because very seldom do we get a commissioner to show up in the middle of Maurice River Township. I’m very thankful to the senator and to the commissioner.

“We do have to drill down and get to some of the nuts and bolts of these projects,” Whilden said. “The cost, and how they’re going to be funded.”

Frustrations bubbled up around the table following the tour.

Ben Stowman, chair of the Maurice River Land Use Board, noted the township was cut out of participation in a recent study of storm risks and mitigation.

The study focused on the Jersey Shore’s “back bays,” including Cape May County but nothing in Cumberland County. The Army Corps of Engineers released a draft study report earlier in August.

“And it’s kind of come back to bite us in this area time and time again,” Bowman said. LaTourette appeared surprised. “Were not included?” he asked.

“Even after we asked,” Maurice River Mayor Ken Whildin said. Later, Whildin confronted LaTourette with a recent state decision to spend $19 million to buy almost 100 acres of undeveloped land in Cape May County. The purchase would end decades of expensive court battles, LaTourette said. Whilden said his township could do a lot with that much money. “It just doesn’t seem fair,” he said. “I can understand that,” LaTourette said.

The most emergent problem, within Maurice River Township, may be a dike at Matts Landing. Behind it are a string of marinas, which lease their sites from the DEP. The township is in talks to take ownership of the land from the state.

The dike is the only barrier to floods reaching communities and maritime businesses on the township side of the Maurice River. Upriver are operations like Yank Marine Services in Dorchester and Allen Steel Co. in Leesburg. And presently, the dike is breached in two spots.

During the tour preceding the meeting, LaTourette was taken to the dike and its history, function, and shortcomings broken down for him.

“This is the only thing that is protecting all the infrastructure that these guys worked so hard for up in Haleyville,” Downe Township Mayor Mike Rothman said. “All the shipbuilding stuff that’s here now. This is it.” Rothman operates a tour boat along the river. “If this goes, this whole river disappears,” he said of the dike.

Maurice River Committeeman Joe Sterling said the dike and its surrounds once had the additional protection of low-lying meadows.

The meadows lay between where the dike now is and the winding Maurice River. The area, still known as “Basket Flats,” an oyster trade reference, now is submerged. There are plans to address that by filling the former meadow area to create dry land, but there is no timetable or an agency assigned for the job.

Additionally, changes in the course of the river increasing direct its current toward the dike. “If we have one good storm, it’s going to wipe this out,” Sterling said.

“We’re going to lose our marina district – what little we have left,” Whildin said during the tour. “And that’s going to affect both sides of the river, because we’ll really both be on a mud flat. So, the ship repair industry that we have on our side will be unavailable to vessel traffic. It won’t be deep enough water.”

Whildin said some local ship maintenance businesses are in position, and expect, to bring in new customers from planned off-shore wind turbine power facilities.

At the meeting, LaTourette said communities will have to make tough choices on what mitigation projects to pursue. Money will never be as available as officials desire, he said.

“But what if there’s $2 (million)?” LaTourette said. “What of all those features do you pick and why? That’s the conversation you will need to have, and we can help you. But that’s what a vulnerability assessment and a resilience planning exercise will do.”

Rothman reminded LaTourette of this area’s history of different treatment compared to how New Jersey responds to projects for other shore communities.

“Whenever it comes to our communities on the bay shore, it’s like Mayor Campbell said (?), we always get met with the different approach because we’re the ‘bay shore,’” Rothman said. “We’re not the coast. We’re not towns with rollercoasters and casinos and fancy restaurants.” Rothman said officials here are tired of having to make excuses to residents for inaction. “But we continue to come to this table,” Rothman said. “And we continue to have the conversation.”

Testa said the economic value of bay shore businesses is underreported and should factor in New Jersey’s decisions.

“The industries that exist here, that are kind of just flying under the radar, if they’re gone, they’re gone forever,” Testa said. “Right? So, oysters are an integral part of our environment and they need to be protected because of the job that they do for our waterways each and every year.”

According to the U.S. Coast Guard, the Maurice River flows into the northeast corner of Maurice River Cove 17 miles north-northwestward of Cape May Light. East Point, on the east side of the entrance, is marked by a light. A Coast Guard summary states that large shellfish plants are along the lower part of the river; shipbuilding facilities are at Dorchester. The summary states Maurice River is entered through a partially dredged crooked channel east of Fowler Island, which is in about the middle of the river’s mouth. The northernmost section passing east of the island has natural depths, it states.

Joe Smith is a N.E. Philly native transplanted to South Jersey more than 30 years ago, keeping an eye now on government in South Jersey. He is a former editor and current senior staff writer for The Daily Journal in Vineland, Courier-Post in Cherry Hill, and the Burlington County Times.

Have a tip? Reach out at (856) 563-5252 or [email protected] or follow me on Twitter,

@jpsmith-dj. Help support local journalism with a subscription.

Joseph P. Smith Vineland Daily Journal – 12/31/2021

DOWNE – Nantuxent Creek is getting its first man-made scouring in a $1.6 million effort to reverse what a decade of big storms have done to clog a key passage for commercial fishing and recreational boats using the Delaware Bay.

The New Jersey Department of Transportation on Wednesday disclosed the start of work. Its Office of Maritime Resources is leading the project in collaboration with several N.J. Department of Environmental Protection maritime and wildlife programs.

The storms that helped silt up the Nantuxent also battered Money Island, a small village at its entrance. Money Island is a principal port for boats supplying packing houses in nearby Port Norris with bay oysters. The project has some direct benefits for the island.

Bay shore frustrations bubble over in meeting with NJ commissioner

Joseph P. Smith Vineland Daily Journal - 12/31/2021

MAURICE RIVER – New Jersey’s top environmental official says the state is not ready to pay for immediate storm protection projects in this stretch of Delaware Bay shore, despite local officials reporting worsening safety conditions.

N.J. Department of Environmental Protection Commissioner Shawn M. LaTourette toured some trouble spots along the Maurice River last week. That was a popular move on his part among local officials, who still ended the day in disappointment.

LaTourette turned back requests to commit to anti-flooding projects, counseling instead greater planning coordination for a "holistic" view on the local level. Communities need to prepare for when money might become available, he said.

Maurice River Township hosted the tour and meeting, working with state Sen. Michael Testa, R-1, to arrange them. Representatives from Commercial and Downe townships and Cumberland County also attended.

"New Jersey’s top environmental official says the state is not ready to pay for

immediate storm protection projects in this stretch of Delaware Bay shore,

despite local officials reporting worsening safety conditions."

“It was very good that he showed up,” Mayor Ken Whilden said afterward. “Because very seldom do we get a commissioner to show up in the middle of Maurice River Township. I’m very thankful to the senator and to the commissioner.

“We do have to drill down and get to some of the nuts and bolts of these projects,” Whilden said. “The cost, and how they’re going to be funded.”

Frustrations bubbled up around the table following the tour.

Ben Stowman, chair of the Maurice River Land Use Board, noted the township was cut out of participation in a recent study of storm risks and mitigation.

The study focused on the Jersey Shore’s “back bays,” including Cape May County but nothing in Cumberland County. The Army Corps of Engineers released a draft study report earlier in August.

“And it’s kind of come back to bite us in this area time and time again,” Bowman said. LaTourette appeared surprised. “Were not included?” he asked.

“Even after we asked,” Maurice River Mayor Ken Whildin said. Later, Whildin confronted LaTourette with a recent state decision to spend $19 million to buy almost 100 acres of undeveloped land in Cape May County. The purchase would end decades of expensive court battles, LaTourette said. Whilden said his township could do a lot with that much money. “It just doesn’t seem fair,” he said. “I can understand that,” LaTourette said.

The most emergent problem, within Maurice River Township, may be a dike at Matts Landing. Behind it are a string of marinas, which lease their sites from the DEP. The township is in talks to take ownership of the land from the state.

The dike is the only barrier to floods reaching communities and maritime businesses on the township side of the Maurice River. Upriver are operations like Yank Marine Services in Dorchester and Allen Steel Co. in Leesburg. And presently, the dike is breached in two spots.

During the tour preceding the meeting, LaTourette was taken to the dike and its history, function, and shortcomings broken down for him.

“This is the only thing that is protecting all the infrastructure that these guys worked so hard for up in Haleyville,” Downe Township Mayor Mike Rothman said. “All the shipbuilding stuff that’s here now. This is it.” Rothman operates a tour boat along the river. “If this goes, this whole river disappears,” he said of the dike.

Maurice River Committeeman Joe Sterling said the dike and its surrounds once had the additional protection of low-lying meadows.

The meadows lay between where the dike now is and the winding Maurice River. The area, still known as “Basket Flats,” an oyster trade reference, now is submerged. There are plans to address that by filling the former meadow area to create dry land, but there is no timetable or an agency assigned for the job.

Additionally, changes in the course of the river increasing direct its current toward the dike. “If we have one good storm, it’s going to wipe this out,” Sterling said.

“We’re going to lose our marina district – what little we have left,” Whildin said during the tour. “And that’s going to affect both sides of the river, because we’ll really both be on a mud flat. So, the ship repair industry that we have on our side will be unavailable to vessel traffic. It won’t be deep enough water.”

Whildin said some local ship maintenance businesses are in position, and expect, to bring in new customers from planned off-shore wind turbine power facilities.

At the meeting, LaTourette said communities will have to make tough choices on what mitigation projects to pursue. Money will never be as available as officials desire, he said.

“But what if there’s $2 (million)?” LaTourette said. “What of all those features do you pick and why? That’s the conversation you will need to have, and we can help you. But that’s what a vulnerability assessment and a resilience planning exercise will do.”

Rothman reminded LaTourette of this area’s history of different treatment compared to how New Jersey responds to projects for other shore communities.

“Whenever it comes to our communities on the bay shore, it’s like Mayor Campbell said (?), we always get met with the different approach because we’re the ‘bay shore,’” Rothman said. “We’re not the coast. We’re not towns with rollercoasters and casinos and fancy restaurants.” Rothman said officials here are tired of having to make excuses to residents for inaction. “But we continue to come to this table,” Rothman said. “And we continue to have the conversation.”

Testa said the economic value of bay shore businesses is underreported and should factor in New Jersey’s decisions.

“The industries that exist here, that are kind of just flying under the radar, if they’re gone, they’re gone forever,” Testa said. “Right? So, oysters are an integral part of our environment and they need to be protected because of the job that they do for our waterways each and every year.”

According to the U.S. Coast Guard, the Maurice River flows into the northeast corner of Maurice River Cove 17 miles north-northwestward of Cape May Light. East Point, on the east side of the entrance, is marked by a light. A Coast Guard summary states that large shellfish plants are along the lower part of the river; shipbuilding facilities are at Dorchester. The summary states Maurice River is entered through a partially dredged crooked channel east of Fowler Island, which is in about the middle of the river’s mouth. The northernmost section passing east of the island has natural depths, it states.

Joe Smith is a N.E. Philly native transplanted to South Jersey more than 30 years ago, keeping an eye now on government in South Jersey. He is a former editor and current senior staff writer for The Daily Journal in Vineland, Courier-Post in Cherry Hill, and the Burlington County Times.

Have a tip? Reach out at (856) 563-5252 or [email protected] or follow me on Twitter,

@jpsmith-dj. Help support local journalism with a subscription.

Historic NJ lighthouse battered by rising seas, now shuttered over contract dispute

ANDREW S. LEWIS | FEBRUARY 8, 2021 | ENERGY & ENVIRONMENT

East Point Lighthouse closed indefinitely as nonprofit custodian refuses to sign state’s new interim license agreement

East Point Lighthouse on the Delaware Bay in Cumberland County. The cracked and perpetually soaked two-lane road leading to New Jersey’s 162-year-old East Point Lighthouse is gradually going underwater. But, on drier days, even in winter, that doesn’t stop tourists from making the long trek to this remote piece of history clinging to the low edge of Cumberland County’s Delaware Bay shore. For now, though, all they can do is look in from the outside.

What the eroding land and rising water has been unable to completely consume, however, may now be in peril due to a dispute with the state Department of Environmental Protection over the landmark’s management lease. Last March, the lease between the state — which owns the lighthouse and its grounds — and the Maurice River Historical Society, the nonprofit organization that has managed the property since 1972, expired. Instead of renewing the lease under the same terms, the DEP in January informed the society that it would need to sign an “interim license agreement” that the society believes is designed to kick it out.

The agreement would be “like signing both the lighthouse and the society’s death warrant,” said Nancy Patterson, president of the society. The DEP said that’s not the intention. “To maintain our partnership with Maurice River Historical Society and to provide continuity of stewardship for the lighthouse, NJDEP is willing to negotiate a new long-term lease with the historical society,” DEP spokesperson Caryn Shinske said.

“Until such an agreement could be reached, the DEP offered Maurice River Historical Society an interim license agreement to ensure their continued involvement with the lighthouse, pending agreement on a long-term lease.”

‘Backed into the corner’ The society has kept the lighthouse closed since mid-January because of the disagreement, unwilling to reopen the doors in the absence of a signed lease with the state that both parties can agree on.

Patterson’s core concern with the five-year interim agreement is that it includes a provision that says the state can at any time terminate its partnership with the society and be entitled to any funds the society has generated — through gift shop sales, grants, donations, etc. — expressly for the upkeep of the lighthouse. “If we sign it, then they could kick us out and take all our money; if we don’t sign it, they could kick us out because we don’t have a license agreement,” Patterson said, noting that the historical society pays for the property’s insurance, electric bills, general maintenance, and promotion. “We’re absolutely backed into the corner.” (The Coast Guard pays for the lantern’s upkeep.) A lease allows a tenant to retain some right to ownership of the property — for example, to add lawn ornamentation or sublet to a third party. A license agreement, however, affords the owner strict control, merely giving the tenant permission to conduct an action — give tours to the public, for example — on the property.

Nancy Patterson of the Maurice River Historical Society points to an area on the lighthouse property where the bay often breaches during high tide.“As written, they’re basically saying ‘This is our land and we’re going to let you on it to do the following — run a store, make repairs, maintain the property — but at any time, if we feel like it, we can kick you off again,’” said Terry Bennett, a lawyer who is consulting with the historical society on the issue. “The implication is that the DEP would need some cause to do this, but their cause might be that they really just don’t want you there anymore.”

Bennett is helping the historical society draft a response to the DEP, outlining its concerns with the interim agreement, that it will submit this week, in the hope that the department will be open to negotiation.

‘A big bowl of water with no place to go’ In 2017, a mult-imillion-dollar, federal- and state-funded project restored East Point to its 19th century stature, but that did nothing for the disappearing shoreline surrounding the lighthouse’s granite foundation and perpetually flooded basement. Originally built 500 feet back from the water, today it’s less than 100 feet from the high tide line.

In 2019, the state invested $460,000 in a 570-foot geotube berm, an 8-foot-diameter tube made of synthetic material and filled with sand. The project was a Band-Aid intended to stave off inundation until a longer-term solution — such as elevating the lighthouse or moving it altogether — could be implemented. As soon as it was installed, however, the geotube proved ineffective during highwater storm events, which on this stretch of Delaware Bay shore, are a common occurrence.

Patterson says the berm was not high enough. “The DEP is always screaming about sea level rise, and they didn’t even build the geotube as high as the natural dune had been before Hurricane Sandy, so the bay goes right over it,” she said. “Now, East Point is a big bowl of water with no place to go.” (As part of its Protecting Against Climate Threats initiative, the state is in the process of updating land-use regulations to account for future sea-level rise.)

After Hurricane Isaias caused serious flooding at East Point in August, the historical society drew up an emergency plan to build more berms around the property, install a wooden walkway, and spread crushed shell on the dirt lane leading to the lighthouse’s parking lot.

“The DEP is always screaming about sea level rise, and they didn’t even build the geotube as high as the natural dune had been before Hurricane Sandy, so the bay goes right over it..."

Political help It was a long shot, Patterson said, given that in the past the DEP had denied many of the society’s requests to conduct its own flood protection projects. But after she contacted Sen. Michael Testa (R-Cumberland) for help, Patterson said she was told by the DEP that the emergency plan had been authorized.

The good news came just after Christmas. Patterson celebrated; donations for the project started pouring in. But less than two weeks later, she was sent the interim agreement. Without an active occupancy agreement and unwilling to sign the interim agreement, Patterson feared that conducting work of any kind on the property could be interpreted by the DEP as a breach of contract, so the society postponed the emergency plan and closed the lighthouse, museum and gift shop indefinitely.

Patterson alerted Testa, as well as U.S. Rep. Jeff Van Drew (R-NJ), of her concerns over the interim license. Testa contacted the DEP’s acting commissioner Shawn LaTourette. “Nancy has put her heart and soul into doing everything that she possibly can to preserve the lighthouse,” Testa said. “I want the experts to get in there and determine what the best long-term plan is to save it.” Testa noted that he and Senate President Steve Sweeney (D-Gloucester) agree that East Point needs to be protected as both a historical site and a place for tourists to visit. “I’m hoping all parties can come together and build a consensus as to what the plan for East Point is going to be,” he said.

“It seems like they want to just be able to close it up,” Patterson said. “And for us to go away.”...

Major mitigation project one mile away A mile to the northwest, at the other end of the wide, shallow mouth of the Maurice River, one of the most ambitious sea-level-rise mitigation efforts ever undertaken on New Jersey’s Delaware Bay shore is set to begin. The American Littoral Society, which is leading the project, has secured $4.8 million in federal funds to begin a $12 million project that will build breakwaters and rock revetments to both absorb storm surge and reestablish shoreline that has disappeared over the last three decades. The remaining $7 million would need to come from a state match “that’s not yet secured,” said Tim Dillingham, the Littoral Society’s executive director. The structures would protect the historic port of Bivalve, where the majority of the bay’s oyster fleet is docked, from the encroaching bay.

“Just like Bivalve, East Point is an irreplaceable, historic resource, and it’s vulnerable and being worn away,” Dillingham said. “Something needs to be done.”

While the Littoral Society has included in its plans an additional phase that would include a breakwater to protect East Point’s highly exposed, west-facing shore, it would require additional funding beyond the current $12 million price tag.

Dillingham hopes they can find the extra money. “This is a critical project at a critical time,” he said. “There really isn’t a lot of time to waste anymore.”

Meanwhile, East Point sits shuttered and in legal limbo, a red-and-white monolith balanced on an ever-shifting landscape. “The DEP is currently assessing its options on how the interior of the structure may be made accessible to the public and remains committed to working with [the historical society] should it reconsider its decision [to not sign the interim license],” the DEP’s Shinske said. “The lighthouse grounds remain open to the public.”

“It seems like they want to just be able to close it up,” Patterson said. “And for us to go away.”

ANDREW S. LEWIS | FEBRUARY 8, 2021 | ENERGY & ENVIRONMENT

East Point Lighthouse closed indefinitely as nonprofit custodian refuses to sign state’s new interim license agreement

East Point Lighthouse on the Delaware Bay in Cumberland County. The cracked and perpetually soaked two-lane road leading to New Jersey’s 162-year-old East Point Lighthouse is gradually going underwater. But, on drier days, even in winter, that doesn’t stop tourists from making the long trek to this remote piece of history clinging to the low edge of Cumberland County’s Delaware Bay shore. For now, though, all they can do is look in from the outside.

What the eroding land and rising water has been unable to completely consume, however, may now be in peril due to a dispute with the state Department of Environmental Protection over the landmark’s management lease. Last March, the lease between the state — which owns the lighthouse and its grounds — and the Maurice River Historical Society, the nonprofit organization that has managed the property since 1972, expired. Instead of renewing the lease under the same terms, the DEP in January informed the society that it would need to sign an “interim license agreement” that the society believes is designed to kick it out.

The agreement would be “like signing both the lighthouse and the society’s death warrant,” said Nancy Patterson, president of the society. The DEP said that’s not the intention. “To maintain our partnership with Maurice River Historical Society and to provide continuity of stewardship for the lighthouse, NJDEP is willing to negotiate a new long-term lease with the historical society,” DEP spokesperson Caryn Shinske said.

“Until such an agreement could be reached, the DEP offered Maurice River Historical Society an interim license agreement to ensure their continued involvement with the lighthouse, pending agreement on a long-term lease.”

‘Backed into the corner’ The society has kept the lighthouse closed since mid-January because of the disagreement, unwilling to reopen the doors in the absence of a signed lease with the state that both parties can agree on.

Patterson’s core concern with the five-year interim agreement is that it includes a provision that says the state can at any time terminate its partnership with the society and be entitled to any funds the society has generated — through gift shop sales, grants, donations, etc. — expressly for the upkeep of the lighthouse. “If we sign it, then they could kick us out and take all our money; if we don’t sign it, they could kick us out because we don’t have a license agreement,” Patterson said, noting that the historical society pays for the property’s insurance, electric bills, general maintenance, and promotion. “We’re absolutely backed into the corner.” (The Coast Guard pays for the lantern’s upkeep.) A lease allows a tenant to retain some right to ownership of the property — for example, to add lawn ornamentation or sublet to a third party. A license agreement, however, affords the owner strict control, merely giving the tenant permission to conduct an action — give tours to the public, for example — on the property.

Nancy Patterson of the Maurice River Historical Society points to an area on the lighthouse property where the bay often breaches during high tide.“As written, they’re basically saying ‘This is our land and we’re going to let you on it to do the following — run a store, make repairs, maintain the property — but at any time, if we feel like it, we can kick you off again,’” said Terry Bennett, a lawyer who is consulting with the historical society on the issue. “The implication is that the DEP would need some cause to do this, but their cause might be that they really just don’t want you there anymore.”

Bennett is helping the historical society draft a response to the DEP, outlining its concerns with the interim agreement, that it will submit this week, in the hope that the department will be open to negotiation.

‘A big bowl of water with no place to go’ In 2017, a mult-imillion-dollar, federal- and state-funded project restored East Point to its 19th century stature, but that did nothing for the disappearing shoreline surrounding the lighthouse’s granite foundation and perpetually flooded basement. Originally built 500 feet back from the water, today it’s less than 100 feet from the high tide line.

In 2019, the state invested $460,000 in a 570-foot geotube berm, an 8-foot-diameter tube made of synthetic material and filled with sand. The project was a Band-Aid intended to stave off inundation until a longer-term solution — such as elevating the lighthouse or moving it altogether — could be implemented. As soon as it was installed, however, the geotube proved ineffective during highwater storm events, which on this stretch of Delaware Bay shore, are a common occurrence.

Patterson says the berm was not high enough. “The DEP is always screaming about sea level rise, and they didn’t even build the geotube as high as the natural dune had been before Hurricane Sandy, so the bay goes right over it,” she said. “Now, East Point is a big bowl of water with no place to go.” (As part of its Protecting Against Climate Threats initiative, the state is in the process of updating land-use regulations to account for future sea-level rise.)

After Hurricane Isaias caused serious flooding at East Point in August, the historical society drew up an emergency plan to build more berms around the property, install a wooden walkway, and spread crushed shell on the dirt lane leading to the lighthouse’s parking lot.

“The DEP is always screaming about sea level rise, and they didn’t even build the geotube as high as the natural dune had been before Hurricane Sandy, so the bay goes right over it..."

Political help It was a long shot, Patterson said, given that in the past the DEP had denied many of the society’s requests to conduct its own flood protection projects. But after she contacted Sen. Michael Testa (R-Cumberland) for help, Patterson said she was told by the DEP that the emergency plan had been authorized.

The good news came just after Christmas. Patterson celebrated; donations for the project started pouring in. But less than two weeks later, she was sent the interim agreement. Without an active occupancy agreement and unwilling to sign the interim agreement, Patterson feared that conducting work of any kind on the property could be interpreted by the DEP as a breach of contract, so the society postponed the emergency plan and closed the lighthouse, museum and gift shop indefinitely.

Patterson alerted Testa, as well as U.S. Rep. Jeff Van Drew (R-NJ), of her concerns over the interim license. Testa contacted the DEP’s acting commissioner Shawn LaTourette. “Nancy has put her heart and soul into doing everything that she possibly can to preserve the lighthouse,” Testa said. “I want the experts to get in there and determine what the best long-term plan is to save it.” Testa noted that he and Senate President Steve Sweeney (D-Gloucester) agree that East Point needs to be protected as both a historical site and a place for tourists to visit. “I’m hoping all parties can come together and build a consensus as to what the plan for East Point is going to be,” he said.

“It seems like they want to just be able to close it up,” Patterson said. “And for us to go away.”...

Major mitigation project one mile away A mile to the northwest, at the other end of the wide, shallow mouth of the Maurice River, one of the most ambitious sea-level-rise mitigation efforts ever undertaken on New Jersey’s Delaware Bay shore is set to begin. The American Littoral Society, which is leading the project, has secured $4.8 million in federal funds to begin a $12 million project that will build breakwaters and rock revetments to both absorb storm surge and reestablish shoreline that has disappeared over the last three decades. The remaining $7 million would need to come from a state match “that’s not yet secured,” said Tim Dillingham, the Littoral Society’s executive director. The structures would protect the historic port of Bivalve, where the majority of the bay’s oyster fleet is docked, from the encroaching bay.

“Just like Bivalve, East Point is an irreplaceable, historic resource, and it’s vulnerable and being worn away,” Dillingham said. “Something needs to be done.”

While the Littoral Society has included in its plans an additional phase that would include a breakwater to protect East Point’s highly exposed, west-facing shore, it would require additional funding beyond the current $12 million price tag.

Dillingham hopes they can find the extra money. “This is a critical project at a critical time,” he said. “There really isn’t a lot of time to waste anymore.”

Meanwhile, East Point sits shuttered and in legal limbo, a red-and-white monolith balanced on an ever-shifting landscape. “The DEP is currently assessing its options on how the interior of the structure may be made accessible to the public and remains committed to working with [the historical society] should it reconsider its decision [to not sign the interim license],” the DEP’s Shinske said. “The lighthouse grounds remain open to the public.”

“It seems like they want to just be able to close it up,” Patterson said. “And for us to go away.”

Menendez, Booker Announce Another $3M to Buyout Flood - Prone Properties in Cumberland County

Thursday, January 16, 2020

WASHINGTON, D.C. – U.S. Senators Bob Menendez and Cory Booker today announced $3,194,446.00 in federal funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to assist with a flood mitigation and resiliency project in Downe Township, Cumberland County.

“Our state was ravaged by Superstorm Sandy and communities are still trying to recover,” said Sen. Menendez. “This grant will help Downe take preventative measures to ensure their residents are safe and that they are prepared when the next major storm hits.”

"We have a responsibility to protect the Delaware Bay from the ever-increasing dangers of rising sea levels and tidal flooding,” said Sen. Booker. “This federal investment in Downe Township is a crucial step toward promoting New Jersey’s flood resilience and emergency preparedness."

The grant will be used to fund the purchase and demolition of 11 flood-prone properties in the Township of Downe. The grant will also assist in the properties’ return to their natural function. The township previously received $5,975,961 in FEMA grants to support the buyout and acquisition of flood-prone properties.

Last year, Sen. Menendez introduced the National Flood Insurance Program Reauthorization and Reform (NFIP Re) Act of 2019, which tackles systemic problems with flood insurance, puts it back on solid fiscal ground, and reframes the nation’s entire disaster paradigm to one that focuses more on prevention and mitigation to spare the high cost of rebuilding after flood disasters.

Press Contact: Chris Flores [email protected]

Tony Novak pictured at one of his properties in Money Island, NJ.

Photo by Craig Matthews, Staff Photographer

Tony Novak pictured at one of his properties in Money Island, NJ.

Photo by Craig Matthews, Staff Photographer

As sea levels rise, one

Delaware Bay community is vanishing

August 3, 2019 -Press of Atlantic City – Avalon Zoppo, Staff Writer

Tony Novak strolls down Nantucket Road in the sweltering heat, as pieces of the Downe Township street erode and fall into the bay. His dog Baxter trots ahead and investigates the remnants of a broken-down mobile home parked on a patch of grass with its contents spilling out.

“It’s been like that for a while,” said Novak, pointing to the unit, which sits next to an abandoned one-story, blue house perched on pilings. His nearby marina is now closed after averaging only one customer per day.